CITA ESTE TRABAJO

Castro Aguilar-Tablada T, Piñero García A. Intestinal ultrasound: Is it time to join our IBD units? How do we do it? RAPD 2024;47(2):72-79. DOI: 10.37352/2024472.3

Introduction

The diagnosis of Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) is based on a combination of clinical, analytical, endoscopic, radiological and histological criteria[1]. We know that it is important to achieve early control of the disease with the intention of achieving mucosal and even transmural healing.

Effective and reproducible monitoring techniques are needed to allow us to closely follow the evolution of the disease. Colonoscopy is a fundamental technique in the management of this disease and is considered the "gold standard" for the diagnosis of UC. However, for patients with CD, endoscopy does not assess transmural or proximal involvement. Furthermore, in up to 20% of cases, colonoscopy is incomplete due to the severity of the disease or the presence of strictures[2]. For this reason, we need to resort to imaging techniques such as intestinal ultrasound, CT and entero-MRI.

In general, both the consensus documents of the Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU)[3], the European Crohn's Disease and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR)[1] consider that both intestinal ultrasound and abdominal CT and MRI have comparable diagnostic accuracy for the initial evaluation of CD, disease severity and assessment of activity and detection of its main complications, strictures, fistulas and abscesses.

Advantages and limitations

The advantages of intestinal ultrasound are:

- It is cheap, cost-effective, accessible and widely available.

- It is the best tolerated test by patients.

- It is non-invasive and harmless.

- It does not require preparation. Although fasting for 4-6 hours is recommended, in general it does not interfere too much with the technique, with the exception of Doppler, which can be artefactual due to the lack of fasting.

- It can be repeated as many times as necessary.

- It provides immediate results.

In addition to the aforementioned advantages, intestinal ultrasound has an additional feature that makes it an unbeatable technique for monitoring IBD, and that is the possibility of performing it during a medical consultation. This is what is known in the literature as POCUS (Point of Care Ultrasonography)[2],[3].

This aspect makes it possible to stratify patients during the consultation, optimise resources by reducing the need for MRI and colonoscopy, speed up decision-making and strengthen the doctor-patient relationship.

Among the limitations, we highlight the following:

- Operator dependent. The learning curve depends mainly on previous experience in abdominal ultrasound.

- It depends on the quality of the ultrasound machine and probes. Conventional 3-5 MHz probes are necessary for an initial general abdominal exploration, but for a detailed exploration of the intestinal loops it is essential to use high frequency probes (5-15 MHz), flat or miniconvex, as they allow a higher resolution assessment of the intestinal wall.

Patient's constitution. Obesity is the fundamental limiting factor[3].

Quantification of the extent. MRI quantifies more precisely the extent of involvement in cases of extensive disease.

Sensitivity depends on the location. Ultrasound may have limitations in the assessment of the rectum, sections of the proximal intestine (jejunum) and the deep pelvis[3].

Ultrasound findings in Crohn's disease

The main ultrasound findings in relation to Crohn's disease include wall thickening, colour Doppler hyperemia, loss of layered structure, ulcers, fibro-fatty proliferation and adenopathy.

Wall thickening:this is considered the key parameter for diagnosis and assessment of activity, with the advantage of low inter-observer variability. There is usually an increase in the thickness of the submucosa (hyperechogenic) over the other layers. The measurement should be made in a longitudinal section, over the anterior wall of the loop and avoiding mucosal folds. The cut-off point is ≥ 3 mm or ≥ 4 mm if high specificity is preferred (S 89.7%, E 95.6% vs S 89%, E 96% respectively). The EFSUMB (European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology) recommends using a cut-off point of 3 mm for higher sensitivity in diagnosis and activity assessment. It is usually accompanied by loop stiffness and loss of peristalsis[2].

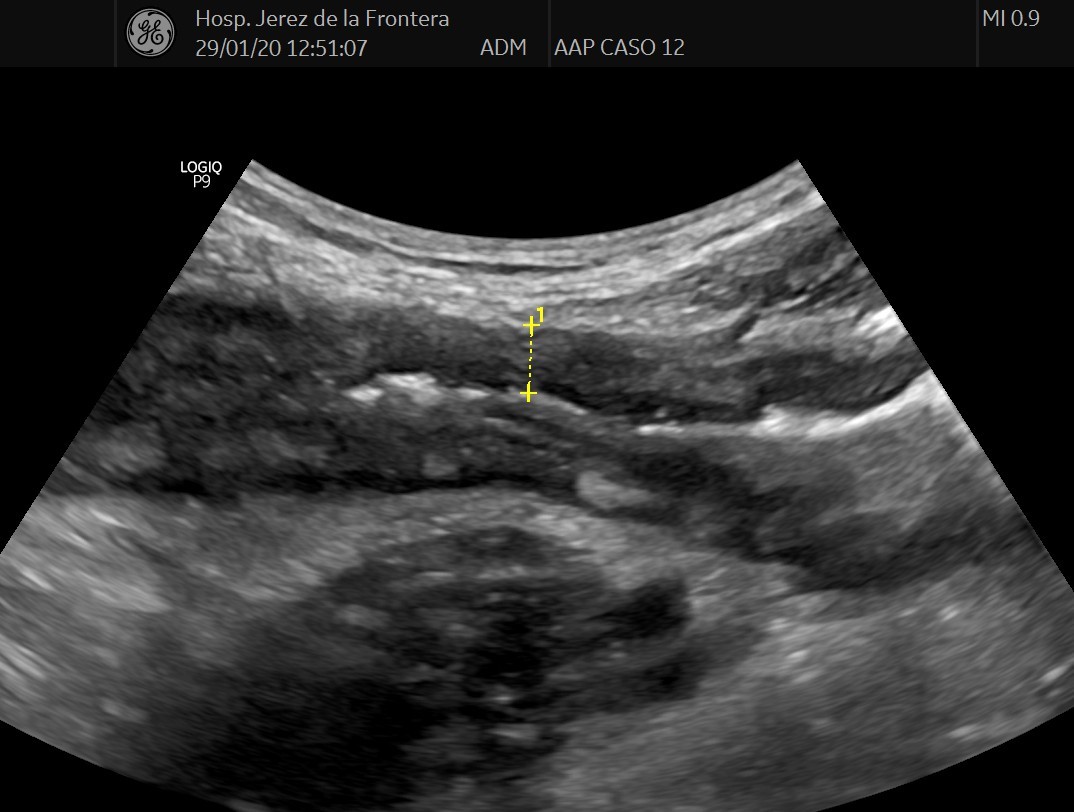

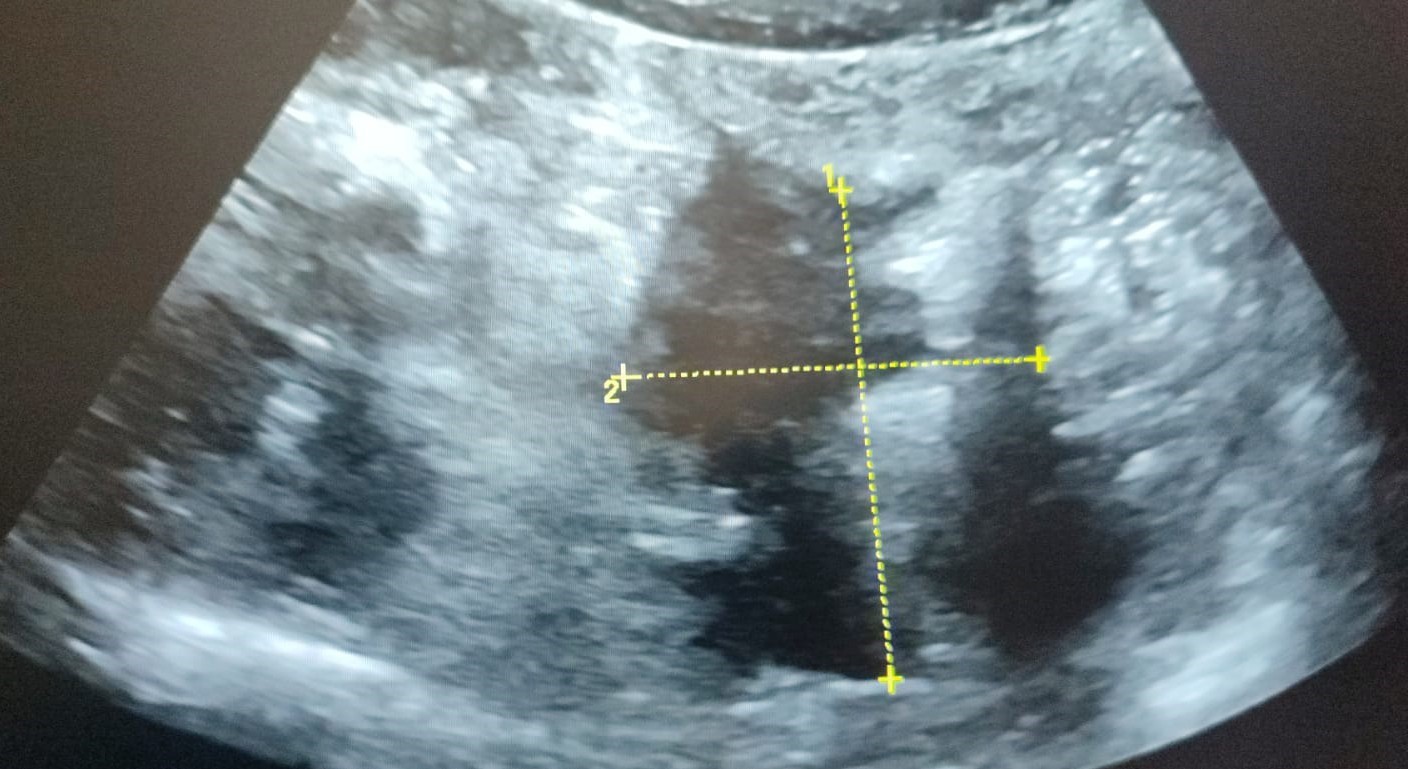

Figura 1

Enfermedad de Crohn. Engrosamiento de la pared de 5,94 mm y conservación de la estructura de capas. El engrosamiento es a expensas de las capas mucosa y submucosa.

Wall hyperemia: hyperemia identified by colour Doppler is another parameter of activity. It is assessed using Limberg's modified semi-quantitative scale that ranks vascularity from 0 (no vascularity) to 3 (intense vascularity) (Figure 2). It has shown a good correlation with histological findings and with clinical and endoscopic activity. A grade 2-3 showed a specificity of over 90% for severe endoscopic disease and a positive predictive value of 97% for the presence of ulcers on endoscopy.

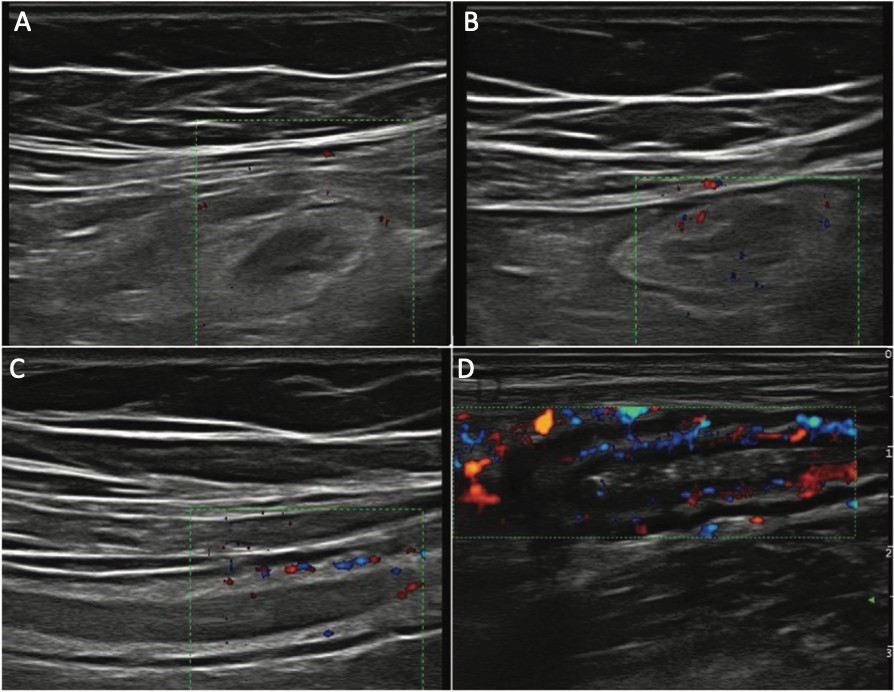

Figura 2

LIMBERG score: A) Grado. 0: sin vasos; B) Grado 1 o apenas visible: 1-2 puntos/cm2; C) Grado 2 o moderado: 3-5 puntos/cm2; D) Grado 3 o intenso: >5 puntos/cm2 o incluso vasos fuera de la pared. Imagen de Muñoz F et al[3].

Loss of layered structure: high-frequency probes allow exploration of the layered structure of the intestinal wall and identify loss of this structure which may be focal, usually secondary to ulcers, or segmental. However, it can sometimes be seen in very advanced latent disease, especially of the left colon, due to severe fibrosis. A correlation has been established with endoscopic activity and increased risk of surgery[4],[5].

Fibro-fatty proliferation: another ultrasound parameter commonly associated with active CD is mesenteric fat involvement. It is characterised by a homogeneous increase in the echogenicity of the fat surrounding a segment affected by the disease. It is associated with wall thickening and fistulas. It may persist in patients in remission[6].

Adenopathies:can be identified in up to 25% of patients with CD, being more frequent in childhood, at diagnosis and in patients with fistulas and abscesses, but are of limited value in assessing disease activity. They usually respond to treatment[2],[7].

Transmural complications

In general the performance of ultrasound is similar to CT or MRI, taking into account the limitation of ultrasound in the assessment of the deep pelvis. The use of oral or intravenous contrast agents may be particularly useful in this clinical context:

- Oral contrast: oral intake of a variable volume (250-800 ml) of an isotonic contrast solution (polyethylene glycol) to distend the loops. Studies using this technique, known as SICUS (small intestine contrast ultrasonography), show a significant contrast ultrasonography), show an increased ability to assess the proximal small bowel, detect strictures and assess postoperative recurrence, as well as reduce interobserver variability. A drawback of this technique is that the duration of the procedure increases from 25 to 45-60 min and complicates the assessment in colour Doppler mode[3].

- Intravenous contrast: the most commonly used ultrasound contrast is SonoVue®, composed of sulphur hexafluoride microbubbles. It is completely intravascular, does not pass into the interstitium, is eliminated via the respiratory tract and has an excellent safety profile. It increases sensitivity in the detection of bowel wall vascularisation compared to the colour Doppler study. It allows the assessment of microvascularisation, whereas Doppler assesses macroscopic vessels[8].

It is necessary to have specific software installed on the ultrasound machine.

There is great variability in the measurements obtained with intravenous contrast from one device to another, so it is recommended, as far as possible, to use the same ultrasound scanner and transducer for monitoring the patient[3].

IV contrast allows us to:

- Visualise the sections of intestinal wall that are inflamed.

- To help differentiate between inflammatory and fibrotic stenosis.

-Differentiate between abscesses and phlegmonous areas.

Transmural complications include inflammatory masses (phlegmon and abscesses), fistulas and strictures.

- Phlegmons/abscesses: abscesses appear as hypoechoic or anechoic masses with posterior reinforcement and well-defined thick walls that may contain gas, while phlegmons appear as hypoechoic masses with poorly defined margins and no identifiable wall. Sometimes their differentiation on B-mode ultrasound is complicated.

The use of intravenous contrast can reliably differentiate them, as phlegmon shows a diffuse enhancement of the lesion while abscesses show peripheral enhancement and an avascular central portion. The use of contrast improves the specificity of the diagnosis of abscess and more accurately defines its size, which may be important in deciding whether the collection requires drainage[9].

- Fistulas: these are identified on ultrasound as hypoechoic tracts extending from the loops to other intestinal segments or other organs, although if they are gassy they may show echogenic foci with or without movement within the tract. The sensitivity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of fistulas is 67%-87%, similar to that of CT or MRI, with a specificity of 90-100%[3].

- Stenosis: Several systematic reviews and consensus documents state that ultrasound, CT and MRI have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of small bowel and colon stenosis, with similar diagnostic yield[10],[11]. In a recently published systematic review the sensitivity of ultrasound was 80% (95% CI, 75.2%-84.2%) and the specificity 95% (95% CI, 89.7%-99.8%)[12]. The use of oral contrast (SICUS) significantly improves the sensitivity of the technique for the diagnosis of low-grade stenosis[13].

According to a recently published consensus document, a stricture can be defined as a thickened (>4 mm), rigid, narrow lumen segment followed by a distended bowel segment anterior to the segment[14].

With oral contrast it is defined when the lumen of the affected bowel segment has a diameter of less than 1 cm, measured at maximum loop distension[15].

Indications for ultrasound in IBD

Intestinal ultrasound plays a key role in the initial diagnosis and follow-up of inflammatory bowel disease, with high sensitivity and specificity in the suspicion of Crohn's disease, in the detection of inflammatory activity and allows early diagnosis of intra-abdominal complications such as strictures, fistulas and abscesses; it has also proven useful in the monitoring of treatment and in post-surgical recurrence.

The ECCO consensus puts MRI and ultrasound at the same level in the initial diagnosis of CD, in the monitoring of treatment, in the monitoring of the asymptomatic patient, and in the detection of complications, although when it comes to abscesses or fistulas located in the pelvis, MRI probably has an advantage. In monitoring cholic involvement and recurrence, colonoscopy would be the choice, although ultrasound could be sparing[1].

Ultrasound monitoring of Crohn's disease

We have seen how ultrasound is useful in the diagnosis of CD, in assessing the extent of the affected area and in detecting complications, but to determine whether it is useful in monitoring the disease, it must be able to detect changes with treatment, quantify them and ensure that the findings are of prognostic interest to allow us to justify treatment adjustments.

Among the studies assessing the usefulness of this technique in the monitoring of CD, the study by Ripollés et al (16), which included 51 patients with CD treated with anti-TNF and followed prospectively for 52 weeks, stands out. They observed that 85% of the patients showed an improvement in ultrasound parameters as early as week 12 and that this predicted the results at week 52. Only 11% of patients with improved ultrasound parameters required intensification or surgery compared to 65% of those who did not experience early improvement.

Which ultrasound parameters change with treatment?

Initial response assessment (with ultrasound or MRI) is recommended within the first 6 months after treatment initiation. The main study demonstrating the usefulness of ultrasound in CD monitoring is the multicentre, prospective TRUST study[17], which followed 234 active patients after treatment for 12 months. Virtually all parameters assessed (thickness, loss of stratification, fibrofatty proliferation, Doppler signal, adenopathy or stenosis) showed improvement by the third month of treatment. Ultrasound changes to assess response may be even earlier, having already been described in ultrasound examinations at 2 or 4 weeks after the start of treatment. In this study, the probability of achieving normal ultrasound parameters was 58%, considerably higher than in previous studies, but less likely in the ileum than in the colon segments.

Can we quantify these changes?

There are different ultrasound indices, but one of the limitations is the lack of quantitative indices that are correctly validated and simple to apply, unlike what happens with MRI (18). Recently, at least three validated indices have been published, including wall thickness and Doppler signal as main variables to try to reduce inter-observer variability.

Does ultrasound change the management of CD?

Ultrasound is a technique that aids in the monitoring of CD and, due to its immediacy, allows decisions to be made immediately on the spot, saving time and resources.

In the study by Novak et al[19], clinical, biological and endoscopic information from 49 patients with CD is provided to two physicians who make a decision on the approach to be taken.

Subsequently, after providing the ultrasound findings, both physicians changed the approach in 60 % of the patients, either therapeutically or by performing other examinations. It should be noted that the ultrasound scan in this study was performed in the consultation room or POCUS itself, so that the change of attitude was made at the same time as the patient was assessed, without waiting.

Therefore, ideally, ultrasound will be scheduled in asymptomatic patients or for treatment monitoring, but in symptomatic patients or those with clearly elevated biomarkers, POCUS or on-the-fly ultrasound would be ideal.

Usefulness of ultrasound in post-surgical recurrence

A particular monitoring situation is recurrence after surgery. In this situation colonoscopy and calprotectin levels are the methods with the highest diagnostic yield, but ultrasound can be a supportive technique. In the meta-analysis by Rispo et al[20] including 536 patients in 10 studies, the sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting recurrence was 94%, with a specificity of 84%. Specificity is lower, 88%, in mild recurrence (Rutgeerts Index i1-i2), and increases to 97.7% in severe recurrence (Rutgeerts Index i3-i4). Wall thickness > 3 mm has been found to correlate with a mild Rutgeerts Index (i1-i2) and wall thickness greater than 5.5 mm usually corresponds to a more severe Rutgeerts Index (i3-i4), and thus colonoscopy can sometimes be avoided.

Treatment objective: mucosal healing vs. parietal healing.

The treatment objective is becoming more and more demanding. Years ago the aim was to keep the patient free of symptoms, then we added the normalisation of biomarkers and nowadays the objective is to achieve mucosal healing and, if possible, also parietal healing.

In order to standardise the ultrasound targets to be achieved, a consensus has recently been published stating that parietal healing would be defined as a wall thickness of 3 mm or less together with no Doppler signal, while ultrasound response includes one of the following criteria: 2 mm reduction in thickness from baseline, 1 mm reduction together with a decrease in Doppler signal of at least 1 degree, or a reduction in thickness of more than 25%[21].

How and when to assess parietal healing?

Both entero-MRI and intestinal ultrasound are appropriate techniques to assess parietal response and healing.

It should be assessed 3-6 months after the start of treatment.

Should it be a therapeutic target?

It is not currently considered a formal therapeutic objective although it should be considered especially in patients with an inflammatory pattern, shorter time of evolution (< 2 years) and with lower wall thickness at the start of treatment (probably less than 5 mm).

Does it have prognostic value?

The prognostic value of parietal healing is superior to mucosal healing in important aspects such as the need for hospitalisation, surgery and therapeutic escalation, although it cannot be achieved in all patients and it must be selected in which group of patients we can achieve it.

As an example, in the study by Castiglione et al[22]the probability of hospitalisation, surgery or recurrence is significantly higher in patients who achieved mucosal healing but with persistent lesions on ultrasound than in those with parietal healing.

Rather than achieving mucosal or parietal healing, it is likely to be a combination of both as the prognosis would still be better.

Usefulness of ultrasound in ulcerative colitis

In UC, the burden of monitoring falls on biomarkers, especially faecal calprotectin and colonoscopy, but ultrasound has a relevant supportive role. The role of ultrasound in UC monitoring is analysed in the TRUST&CU study[23] which includes 224 patients with UC followed prospectively with ultrasound at baseline and at weeks 2, 6 and 12 after initiation of treatment. At week 2 they already found a significant decrease in all parameters analysed. In addition, sigmoid wall thickness at week 2 predicted response to treatment at week 12.

Ultrasound findings in UC are similar to those described in CD, i.e. increased wall thickness, loss of layered stratification, hyperemia, etc., perhaps pointing out the loss of haustration as a characteristic of cholic involvement.

The main limitation of ultrasound in UC is the assessment of the rectum, which is especially relevant when this is the most affected area or when the disease is limited to this location.

Therefore, ultrasound in UC allows us to make a complementary assessment to the clinical and biomarkers, allowing us to have more information for making decisions on treatment or indication of other examinations such as colonoscopy. It also allows us to assess the extent of the disease in situations where colonoscopy has been incomplete due to stenosis, poor preparation or is not recommended due to the severity of the outbreak. And it appears to have a possible role in severe UC flare-ups in predicting response to treatment.

The study by Ilvemark et al[24] included 56 patients with severe UC flare-up who underwent baseline ultrasound at 24-72 hours and found that a decrease of 20% or more in baseline thickness was associated with a favourable response to intravenous corticosteroids, with a sensitivity of 84.2% and a specificity of 78.4%.

Conclusions

Intestinal ultrasound is a good alternative to more invasive imaging techniques, with similar accuracy. In addition to being fast and readily available, it provides real-time feedback and enables early clinical decision making. The use of POCUS can modify the therapeutic and follow-up strategy in up to 60% of patients with CD. It can be used to assess and monitor disease activity and treatment response in UC. Further studies are needed to develop reliable and reproducible activity indices, using colonoscopy and MRI as reference standards.

Intestinal ultrasound: is it time to incorporate it into our IBD units?

It is highly advisable to incorporate ultrasound into IBD units and consultations, but this requires adequate logistical resources and even more necessary to be able to dedicate time to it. We cannot forget that with POCUS three acts are performed in one (consultation, intestinal ultrasound and review), saving time and resources for the benefit of the patient.

Descargar número completo

Descargar número completo Download full issue

Download full issue