CITE THIS WORK

Sanabria Marchante I, Manrique Gil MJ, Rodriguez Ramos C, Macías Rodríguez MA. ¿What does stationary and ambulatory impedance testing contribute to classical measurement techniques? RAPD 2025;48(1):9-17. DOI: 10.37352/2025481.1

Introduction

Multichannel intraluminal impedance testing is a technique that was developed in 1990 at the Helmholtz Institute in Aachen (Germany) and was first described by Silny[1] who studied the movement of the intraluminal bolus by measuring changes in the conductivity of the contents. Its use was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002. The fundamental basis of this technique is that it allows us to detect the direction of movement of the oesophageal intraluminal bolus without the use of ionising radiation.

The review of this topic is divided into:

1.- Concept and basic graph

2.-Indications:

- Impedance associated with High Resolution Manometry (HRIM)

a. Supragastric belching and rumination

b. Achalasia

c. Other

- Impedance coupled to 24-hour pHmetry.

a. Hypersensitive oesophagus

b. Functional pyrosis

3.- Conclusion

Concept and basic graph

Impedance testing measures the greater or lesser resistance to electrical current between two metal electrodes included in the high resolution oesophageal manometry catheter. It is the opposite of conductivity. This resistance will increase according to the oesophageal content, independently of the oesophageal pH. Its fundamental unit is the Ohm (Ω).

Thus, depending on the oesophageal content, we will have a graph with a fall or rise in the impedancemetry, which will indicate the direction. Air has a high impedance (10,000 Ω), while saline has a low impedance (100 Ω). Therefore, this test should be performed with saline swallows whose impedance is known and easily recognisable on the graphs. The resting state of the oesophagus shows the impedance values of its mucosa[2].

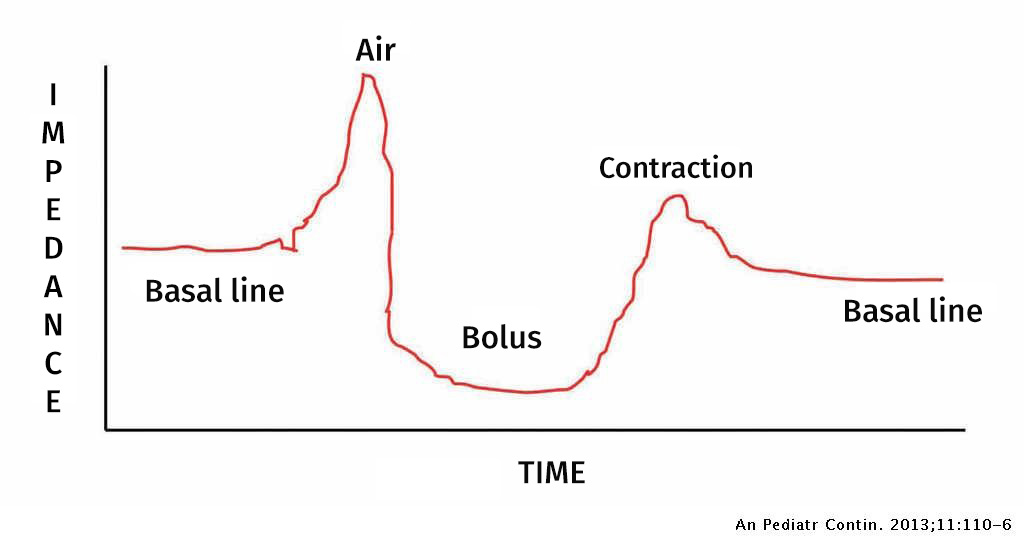

The basic graph to recognise when swallowing is as follows (Figure 1)[3]:

First there is a rise above the basal line which corresponds to the air that we swallow together with the food bolus.

Then the impedance drop due to the arrival of the bolus in the canal is recorded, which should be at least 50% above the baseline.

Finally, recovery of the basal levels takes place.

This occurs in each of the channels located in the tube so that if we look at the direction of the fall or rise we can identify both the type of oesophageal intraluminal contents and its direction.

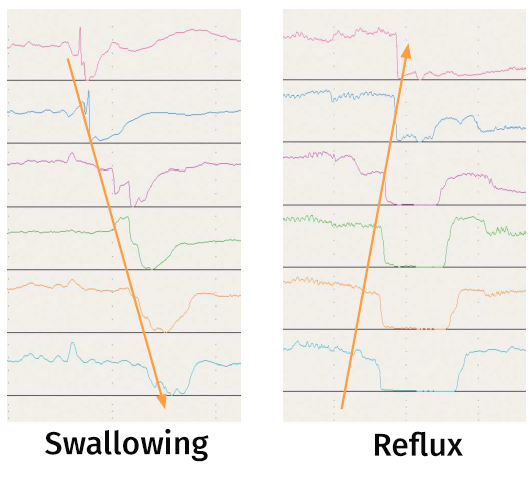

The antegrade movement of the bolus that occurs during swallowing produces a fall in impedance from proximal to distal and subsequently produces the peristaltic wave that we see on oesophageal manometry recordings as usual.

In contrast, retrograde movement of the bolus, which implies a reflux or regurgitation episode, is reflected as an impedance drop from distal to proximal. Esophageal clearance is then observed with a drop from proximal to distal and a corresponding peristalsis wave (Figure 2)[3].

If the content is air, instead of a drop in impedance we would observe a rise in impedance.

However, it should be noted that this technique is very sensitive to small changes in both liquid and gas volumes. It is therefore not possible to estimate the amount of intraluminal fluids as it has been found that the drop is similar with amounts of 1 and 10 ml.

Artefacts, movements on the baseline due to the movement of the catheter, also occur during the study. It is important to be aware of these artefacts and know how to identify them in order to avoid misdiagnosis.

Indications (Table 1)

Table 1

Indications for impedance testing

The indications for impedance testing are under continuous review and study. They are currently well established in the following cases [4]:

- Coupled with high-resolution manometry (HRIM):

a. To evaluate antegrade and retrograde movement in the diagnosis of gastric/supragastric belching and rumination syndrome.

b. To assess the level of oesophageal retention as a substitute for a timed barium oesophagogram in achalasia, especially after treatment.

c. Impedance planimetry system (Endoflip) to assess adequate distensibility in both the oesophageal body and oesophageal-gastric junction.

- 24-hour oesophageal impedance measurement (IMM-pH) to assess non-acid reflux.

There are other indications whose bases are not as widespread but which are commonly used in centres where the technique is available, such as[4]:

- Assessment of oesophageal bolus retention.

- HRIM to assess bolus transit in relation to peristaltic integrity, using the criteria of effective vs. ineffective and the importance of peristaltic ruptures.

- Automated analysis of impedance impedance measurement for the assessment of bolus transit in non-obstructive dysphagia.

- HRIM with videofluoscopy to model the phases of bolus transit and intrabolus pressure classification.

Impedance coupled with high-resolution oesophageal manometry (HRIM)

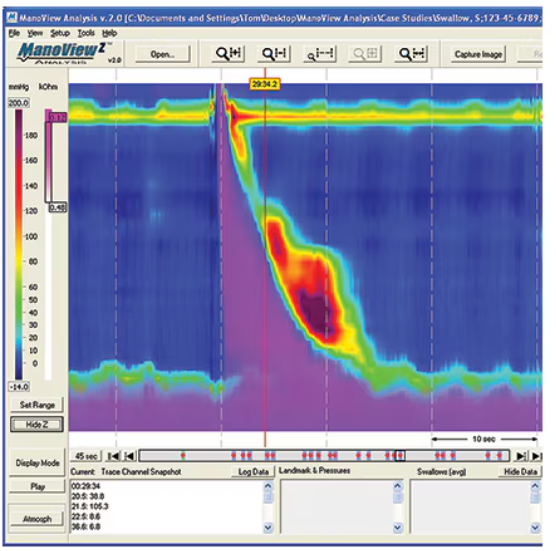

This is an improvement on the basic technique, because in addition to providing information on oesophageal motor alterations, it allows us to know the functional component. In other words, it tells us what oesophageal transit is like. For this purpose, the usual protocol of the manometric study is followed, but taking into account that swallows must be performed with saline (0.9%). In figure 3, a normal recording can be observed with complete clearance of the esophageal contents (purple color).

Its use is already contemplated in the Chicago Classification version 4 published in 2020[5], where it is recommended (although it is not considered essential) to assess intra-bolus pressure, oesophageal clearance and bolus flow through the oesophagogastric junction. This is because there are patients who, despite the clinical manifestations they refer to us, we do not obtain a diagnosis after performing our manometric tests, and this occurs because the functional component is not taken into account. This occurs mainly in rumination disorders and supragastric belching.

These functional pathologies are often underdiagnosed because they cannot be demonstrated by any objective test.

a. Supragastric belching and rumination

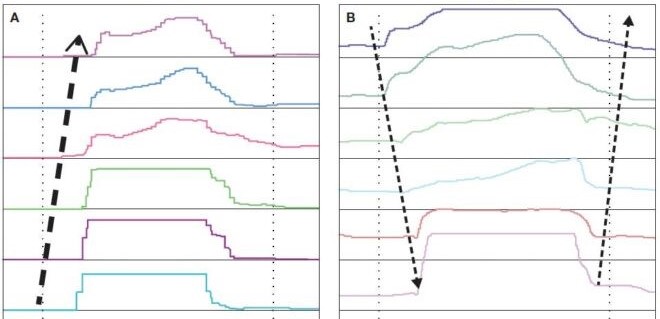

During further study of the graphs we can clearly differentiate gastric belching from supragastric belching (Figure 4)[6].

Rumination is a functional disorder defined by voluntary regurgitation of recently ingested food, followed by re-chewing and swallowing, or expulsion from the mouth. It is not preceded by nausea or straining and ends when the regurgitated material becomes acidic. It is seen in up to 2% of the adult population. There are three types. Primary rumination and secondary rumination, associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux or supragastric belching. Classically, the diagnosis is made in the consultation room, but this requires a very detailed history and a very clear explanation by the patient of the episodes, which is sometimes very difficult to obtain. This is why impedance enables us to observe the episodes as they occur and to obtain a very clear record. Its treatment is far from the drugs that would be used to treat gastro-oesophageal reflux, so these patients are often treated chronically with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) without this resolving their underlying pathology[6],[7]. Definitive treatment, as in the case of supragastric belching, is behavioural with diaphragmatic breathing techniques[8]. In these cases the examination should be performed in a different way. A standardised meal should be provided at the end of the normal recording with solids. Then the postprandial period should be recorded, which is where the episodes usually occur. Thus, in the case of rumination, an increase in intragastric pressure preceding normal swallowing is observed. This, in a normal recording, can be confused with episodes of regurgitation[9].

b. Achalasia

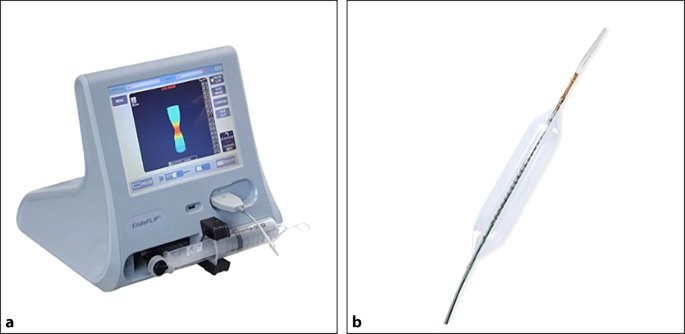

This is a very relevant pathology in our motility units. Its clear diagnosis and, above all, its treatment are a challenge. The patient's quality of life and possible long-term complications require that, whether we decide on oesophageal dilatation or oesophageal myotomy, the result should be as precise as possible. The gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) must have adequate distensibility to allow transit, but without causing dysphagia or gastro-oesophageal reflux[10]. For this purpose, the endoFLIP (impedance planimetry system) was developed (Figure 5). It is a probe in which a highly elastic polyurethane balloon (which assumes a cylindrical shape with volumetric distension) is mounted, equipped with a solid-state pressure transducer to measure intra-balloon pressure, as well as closely spaced impedance electrodes to acquire sectional area measurements along the length of the balloon. There are two probe sizes, 8 and 16 cm. The 8 cm probe only gives information from the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 6) and the 16 cm probe does not complement the distal oesophageal body. The relationship between the cross-sectional area and the pressures inside the balloon can be represented as the distensibility index (DI). DI was initially used to study GEJ, particularly in achalasia, before and after lower oesophageal sphincter intervention, where it was shown that symptomatic oesophageal outcomes correlate with low DI[11]. It can also be used for fundoplication procedures and as training for surgeons. Table 2 summarises the currently validated values and targets for the treatment of different pathologies. It is also possible to use it in other pathologies that mainly affect the GEJ such as eosinophilic oesophagitis or distal oesophageal spasm[4].

Table 2

Interpretation of Endoflip values.

c. Others

This opens up a wide range of diagnostic possibilities and the patient can be classified according to whether he or she has a clearly complete or incomplete transit. Both to diagnose functional pathologies as mentioned above and to avoid diagnoses in healthy patients. This occurs, for example, in the secondary disorders included in the Chicago Classification[5] that do not involve a transit disorder and which until now we have been checking with another complementary test such as the barium transit. Thus, for example, we can observe at the same time that, even if we have a diagnosis of obstructed flow, the transit is complete. And this is reproducible with other diagnoses or doubts in some registries. Studies are underway to determine the prognostic value of bolus pressure and transit alterations[12].

In this respect, different rates and metrics are being developed in order to be able to complete the dysphagia study. Among the most relevant are currently[13]:

Oesophageal impedance integral (EII): The ratio between the presence of bolus before and after a peristaltic wave.

- Normal (where there is no bolus after the peristaltic wave).

- Fragmented peristalsis (where there is some bolus after a peristaltic sequence).

- Absent peristalsis (where the presence of bolus may be similar before and after the peristaltic wave).

The EII ratio in supine HRIM showed a strong correlation with video fluoroscopic findings.

Bolus flow time: The bolus flow time (BFT) represents the decrease in both pressure and impedance across the GEJ, resulting in the passage of the bolus through it.

Impedance nadir point: This is the intrabolus distension pressure that occurs at the point of maximum luminal distension. It corresponds to the point of maximum bolus accumulation. It coincides with the maximum distension in time and space. It allows the measurement of the intrabolus distension pressure during its transport (pressure at the impedance nadir).

Bolus height: When a 200 ml water challenge is administered with the patient standing during an HRIM study, the water column within the oesophagus can be quantified as the impedance bolus height (IBH) at the end of 5 min, using HRIM topography plots showing bolus retention (or lack thereof) in the oesophageal body.

In conclusion, the application of impedance technology to oesophageal HRM, as well as the development of impedance planimetry, especially with FLIP, has increased our understanding of oesophageal motor function and dysmotility. HRIM assesses oesophageal bolus transit with good correlation to videofluoroscopy, but without radiation exposure[14]. The development and better understanding of impedance-based metrics, such as PIB, nadir impedance pressures, EII and BFT ratios, improve our ability to better understand and assess bolus transit dynamics, especially with the development of automated impedance-manometry. HRIM has contributed to the Chicago Classification of oesophageal motor disorders and will likely play an even more important role in future classification interactions.

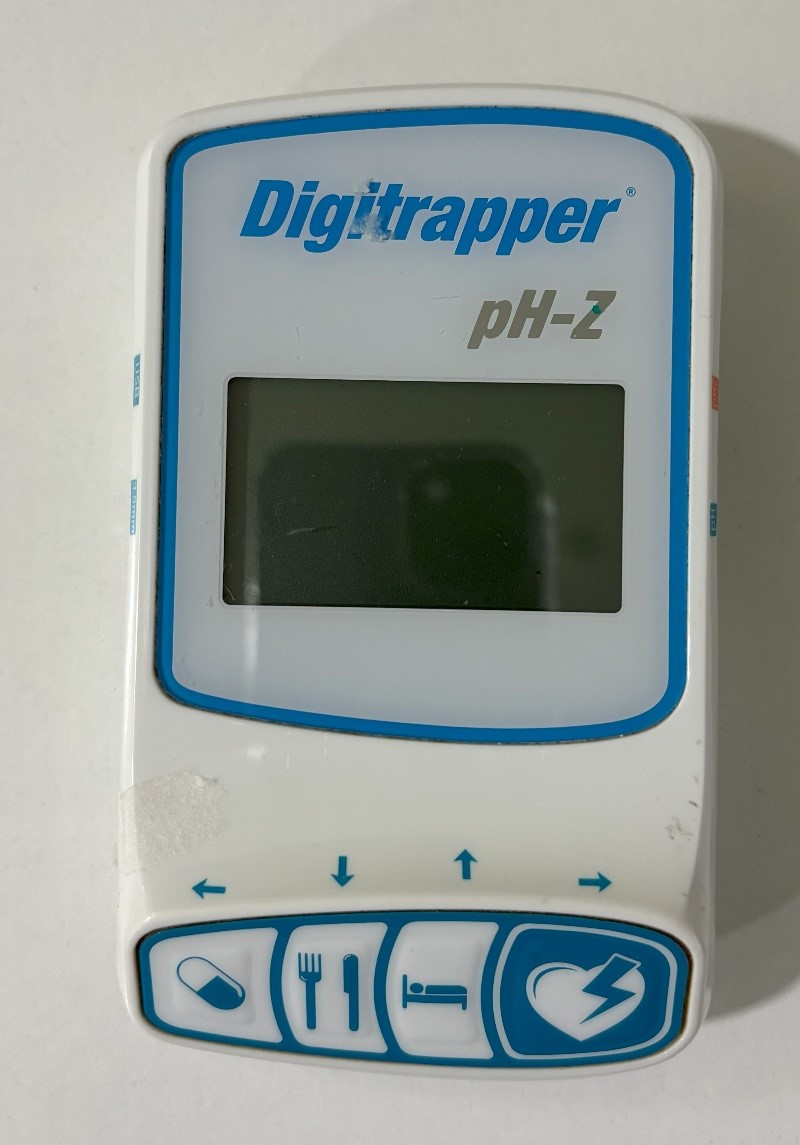

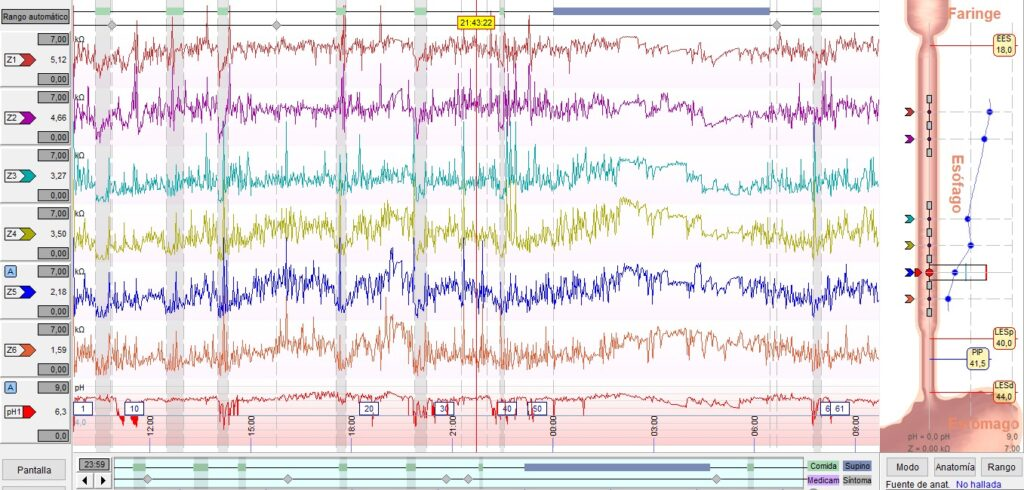

24-hour ambulatory impedance testing

The procedure is very similar to ambulatory oesophageal pHmetry. A 2.1 mm catheter with multiple impedance sensors and an antimony electrode for pH detection is placed transnasally 5 cm from the upper edge of the LES, connected to a recorder or Holter(Figures 7A y 7b). Fasting between 4 and 6 hours is recommended, generally indicating the taking of antisecretory treatment even on the day of the test in cases where a study under treatment is required. Throughout the study period, the following are recorded: meal times, periods in decubitus and standing position, as well as the recommendation to take meals and perform activities that the patient is known to provoke episodes of gastroesophageal reflux[15],[16].

The main indications are[17] (Table 1):

In patients with heartburn or regurgitation unresponsive to twice-daily intensified proton pump inhibitors.

In patients with chest pain, throat or respiratory symptoms in whom gastroesophageal reflux disease is suspected, non-responders to double dosing.

Evaluation of patients with normal acid exposure, but increased episodes of non-acid reflux and/or an association between non-acid reflux and symptoms, increasing the number of patients suitable for anti-reflux surgery.

Patients with recurrent or persistent reflux symptoms after anti-reflux surgery as this may confirm or reject persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux and exclude other causes of symptoms, such as supragastric belching.

The composition of backflow episodes can be classified by MII into gas, liquid or mixed content; as air is a poor conductor of electricity and therefore has a high impedance, as opposed to liquid content which is a good conductor and has a low impedance.The proximal extent of reflux is localised by the changes in impedance of the liquid component recorded at the most proximal sensor.

It allows us to diagnose acidic, weakly acidic and basic reflux and its relation to symptoms. We can then study the different phenotypes, diagnosing hypersensitive oesophagus and functional heartburn[18].

Hypersensitive oesophagus is defined by

Retrosternal symptoms, including heartburn and chest pain.

Normal endoscopy and no evidence that eosinophilic oesophagitis is the cause of symptoms.

Absence of primary motor disorders (PTEMP).

Evidence of physiological GOR triggering symptoms, despite normal acid exposure on oesophageal pHmetry or impedance testing.

Functional heartburn is defined by:

Retrosternal discomfort or pain in the form of burning.

No relief of symptoms despite optimal antisecretory treatment.

No evidence of GOR or eosinophilic oesophagitis as the cause of symptoms.

Absence of PTEMPs.

In addition, they must be observed for at least the last 3 months, with the onset of symptoms at least 6 months prior to diagnosis and with a frequency of at least twice a week[5].

It should be noted that up to 40% of patients do not respond to treatment with PPI. Hypersensitive oesophagus is a condition that studies suggest may occur in 14-20% of patients with typical reflux symptoms. Approximately 10-15% of patients with erosive reflux disease and up to 50% of patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) remain symptomatic despite treatment with PPIs[19].

However, persistent pathological reflux is rare, and MII-pH analysis with PPIs demonstrates normal acid exposure time and low numbers of reflux episodes. In patients with normal acid exposure time (AET) when performing MII-pH, the symptom index (SI) and symptom association probability (SAP) may provide evidence of a clinically relevant association between reflux episodes and symptoms[20].

In addition, this technique has introduced new concepts, such as:

Non-acid reflux:existence of reflux by MII without fluctuation of the oesophageal pH.

Acid reflux:existence of a new reflux episode when the pH detector has not yet normalised the recording to above 4.

Weakly acid reflux:measurement of reflux by MII with a decrease of at least 1 point in oesophageal pH always above 4.

Recently, two metrics have been integrated into the MII-pH analysis: the post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index (PSPW) and more relevant the mean nocturnal basal impedance (MNBI). These are two independent indicators of reflux-mediated symptoms that increase the diagnostic yield of impedance testing. An MNBI <1,500 Ohms supports the diagnosis of GERD, while an MNBI >2,500 Ohms rules it out. A PSPWI may support the diagnosis of GORD, when this index is less than 60%.

Furthermore, in non-responders, the PSPW is significantly lower in refractory oesophagitis compared to healed reflux oesophagitis and NERD. It is the only MII-pH parameter associated with PPI-refractory mucosal damage.

For all these reasons, MII-pH allows us to more accurately diagnose patients with erosive and non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux and, above all, to identify functional disorders and carry out correct treatment[22].

Conclusion

In conclusion, we are faced with a technique in full development in terms of its use, on which different values and metrics are being studied to facilitate the diagnosis of functional pathologies. All this will provide us with a complete understanding of oesophageal function and the clinical picture of our patients. In addition, it is also useful for assessing response to treatment.

Descargar número completo

Descargar número completo Download full issue

Download full issue